What about Richard Wagner? Art and Revolution (II)

This is part 2 of a discussion of Wagner’s 1849 paper Art and Revolution. If you haven’t read part 1, start here.

Wagner then claims explicitly that, in distinction to the fundamentally political and material strivings of the socialists, the great expression of the universalist revolutions must be in Art.

He then begins to speculate on the man and the culture of the future, granting that it is impossible to predict or to dogmatise about how this should look. He reveals a progressive, evolutionist impulse in himself too — history is not a random zigzag, but an ordered stream, bending and looping yet flowing in a mighty course.

Let us glance, then, for a moment at this future state of Man, when he shall have freed himself from his last heresy, the denial of Nature, that heresy which has taught him hitherto to look upon himself as a mere instrument to an end which lay outside himself. When Mankind knows, at last, that itself is the one and only object of its existence, and that only in the community of all men can this purpose be fulfilled: then will its mutual creed be couched in an actual fulfilment of Christ's injunction, "Take no care for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on, for your Heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things."

This Heavenly Father will then be no other than the social wisdom of mankind, taking Nature and her fullness for the common weal of all. The crime and the curse of our social intercourse have lain in this: that the mere physical maintenance of life has been till now the one object of our care, a real care that has devoured our souls and bodies and well nigh lamed each spiritual impulse. This Care has made man weak and slavish, dull and wretched; a creature that can neither love nor hate; a thrall of commerce, ever ready to give up the last vestige of the freedom of his Will, so only that this Care might be a little lightened.

In a dialectical turn, Wagner claims that the completion of Christ’s teaching will come when Christian culture overcomes its denial of Nature, and ultimately of itself, ceasing to seek any end outside of the fullness of its own existence. We see here too traces of Nietzsche’s critique of the Last Man, a man whose focus on bare physical survival and comfort has undermined any capacity for greater spiritual striving. Wagner would not meet Nietzsche until nearly 20 years after this essay was published; Nietzsche was around 5 years old when these words were written.

He then indulges in a fantasy of what, 200 years later, we might call a cyber-communist fantasy:

“When the Brotherhood of Man has cast this care for ever from it, and, as the Greeks upon their slaves, has lain it on machines,−the artificial slaves of free creative man, whom he has served till now as the Fetish−votary serves the idol his own hands have made, then will man's whole enfranchised energy proclaim itself as naught but pure artistic impulse.”

The stakes of a future where Art leads are then laid out in another passage that is fascinatingly proto-Nietzschean:

Only the Strong know Love; only Love can fathom Beauty; only Beauty can fashion Art. The love of weaklings for each other can only manifest as the goad of lust; the love of the weak for the strong is abasement and fear; the love of the strong for the weak is pity and forbearance; but the love of the strong for the strong is Love, for it is the free surrender to one who cannot compel us. Under every fold of heaven's canopy, in every race, shall men by real freedom grow up to equal strength; by strength to truest love; and by true love to beauty. But Art is Beauty energised.

Here is an implicit critique of the standard, Christian love for the weak and the oppressed. Such a love can only spring from pity, for the powerful, and fear and submission, for the weak. The seeds of The Geneaology of Morals are undoubtedly here sowed. The higher love follows an aristocratic ideal, of free choice voluntarily surrendering to leadership by the best.

The final line is also powerful, “Art is Beauty energised”. Beauty in motion, unfolding itself in time and space, not merely transcendentalized or abstracted into a perfect eternal realm. Wagner then sketches his vision of a social structure that would live up to this:

The Goth was bred to battle and to chase, the genuine Christian to abstinence and humility: while the liegeman of the modern State is bred to seek industrial gain, be it even in the exercise of art and science. But when life's maintenance is no longer the exclusive aim of life, and the Freemen of the Futureinspired by a new and deed−begetting faith, or better, Knowledgefind the means of life assured by payment of a natural and reasonable energy; in short, when Industry no longer is our mistress but our handmaid: then shall we set the goal of life in joy of life, and strive to rear our children to be fit and worthy partners in this joy. This training, starting from the exercise of strength and nurture of corporeal beauty, will soon take on a pure artistic shape, by reason of our undisturbed affection for our children and our gladness at the ripening of their beauty; and each man will, in one domain or other, become in truth an artist.

In opposition to the modern education, wherein even training in Art and Science is bent towards the needs of Industry, Wagner imagines an education where the aim is “joy in life”. From physical beauty to spiritual beauty, following a classical, Renaissance idea that flesh is not to be mortified or negated, but cherished. It is a profoundly yogic vision, a training in the “arts of life”. He concludes with the view that the apex of this artistic training will be the Tragic Theatre: “

And as the Knowledge of all men will find at last its religious utterance in the one effective Knowledge of free united manhood: so will all these rich developments of Art find their profoundest focus in the Drama, in the glorious Tragedy of Man. The Tragedy will be the feast of all mankind; in it, set free from each conventional etiquette, free, strong, and beauteous man will celebrate the dolour and delight of all his love, and consecrate in lofty worth the great Love−offering of his Death.

Tragedy stands as the great sacrament of life, the final spiritual statement of mankind to mankind, sacralizing death not in afterlife or resurrection, but in the beauty of finite existence with all its pain.

Wagner then lashes out at his critics who call his vision Utopian — the practical men, who lack capacity for imagination beyond calculation and violence, and the transcendentalists, who he frames as merely themselves addicted to the nakedest brutalities of the material world, incapable of conceiving a more beauteous immanent life. He concludes that the Christians would destroy the world if only they could, to prove the existence of their “solitary abstract God”. All that holds them back is the strength of human nature itself — a remarkable statement of the Romantic ideal.

Then we return to the theme of the industrialization of Art, attacking the pure commercialisation of the Stage. “If the Theatre is at all to answer to its natural lofty mission, it must be completely freed from the necessity of industrial speculation.”

An interesting aside — there are interesting interviews with George Lucas, creator of Star Wars, on YouTube where he speaks with envy of the Soviet film industry and his friends and colleagues there. Soviet filmmaking, freed from the commercial incentive, is capable of the deeply spiritual and reverent works, such as those of Andrei Tarkovsky. What is sacrificed in virtue of the inability to critique the Party bureacracy directly, is made up for by the funds that are distributed to the talented to realize their Art. Star Wars, by contrast, was crafted to the strict demands of the commercial film industry.

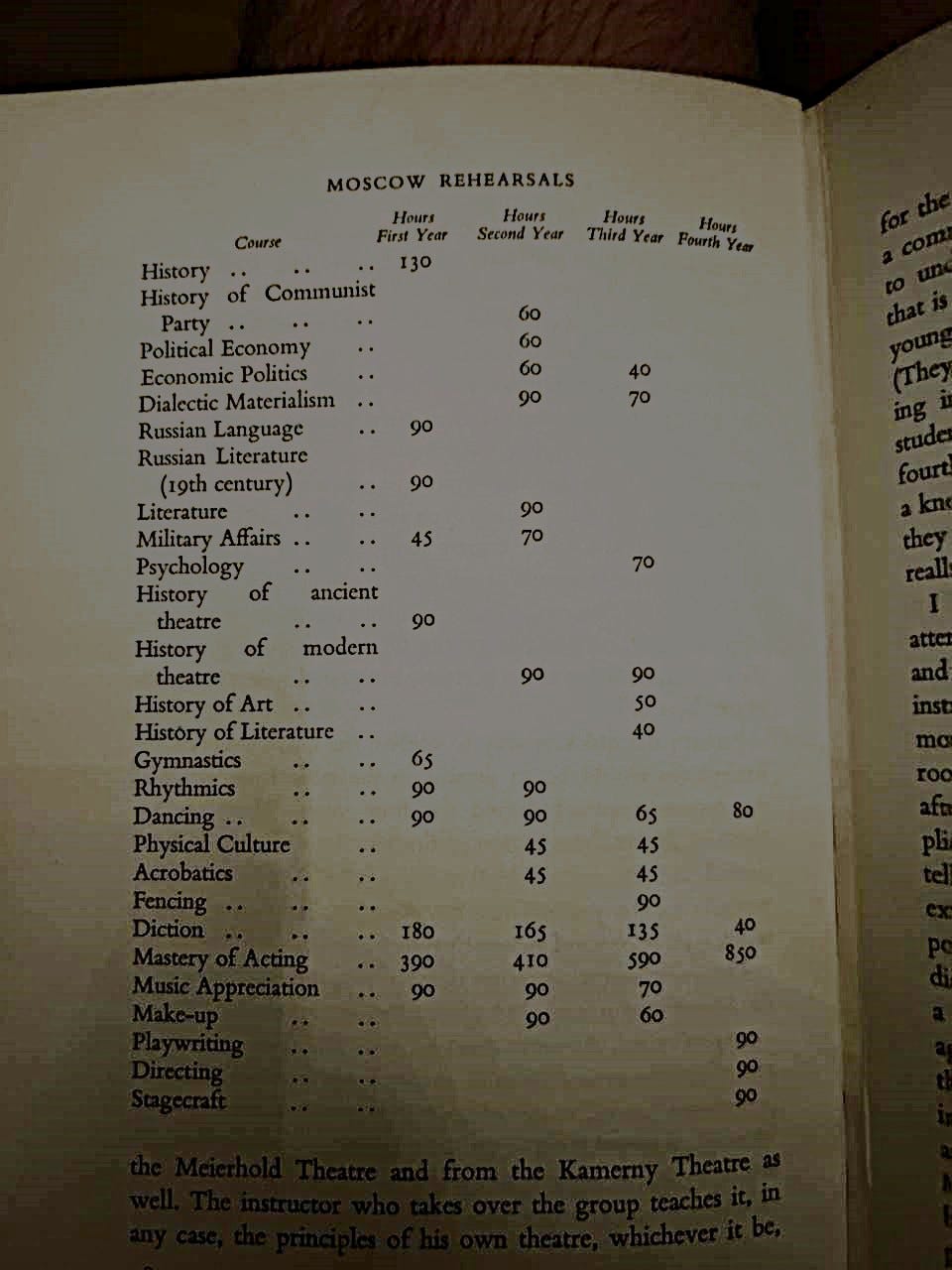

I have also been reading a study of the Soviet Theatre from the mid 1930s, where the author admires the dedication and reverence that the Art receives within society. The Theatres are funded, and vigorously attended by the masses. Furthermore, the rural factories maintain dramatic clubs, and promising upstarts are selected by the managers and sent to Moscow for audition and vigorous training. The training program (even more remarkable for the fact that it was often delivered to illiterate proletarians with no other cultural training) is worth looking at.

There may be much of the Soviet system we wish never to repeat. But the strength of their education programs (which continue today in many areas East of the Rhine) cannot be ignored, especially in the face of a Western education system which has increasingly been whored out to short term post-industrial pressures.

Wagner seems to agree.

How were this possible? Shall this solitary institution be released from a service to which all men, and every associate enterprise of man, are yoked to−day? Yes: it is precisely the Theatre, that should take precedence of every other institution in this emancipation; for the Theatre is the widest−reaching of Art's institutes, and the richest in its influence; and till man can exercise in freedom his noblest, his artistic powers, how shall he hope to become free and self−dependent in lower walks of life? Since already the service of the State, the military service, is at least no longer an industrial pursuit, let us begin with the enfranchisement of public art; for, as I have pointed out above, it is to it that we must assign an unspeakably lofty mission, an immeasurably weighty influence on our present social upheaval. More and better than a decrepit religion to which the spirit of public intercourse gives the lie direct more effectually and impressively than an incapable statesmanship which has long since host its compass: shall the ever−youthful Art, renewing its freshness from its own well−springs and the noblest spirit of the times, give to the passionate stream of social tumult, now dashing against rugged precipices, now lost in shallow swamps, a fair and lofty goal, the goal of noble Manhood.

“The enfranchisement of Public Art”, a goal as noble, worthy and necessary for the polis as the military. Of course we may speculate how to achieve this, without the Public Art simply becoming the propagandist mouthpiece of a ruling mass-slave ideology and bureaucratic party. We will return to this theme, as it is absolutely crucial for our beloved 21st century renaissance.

Wagner then cries out to the men of his day to lend their strength and resources to the cause, that the violent revolutions may be dignified by a renewal of the Arts for all men, and that those who suffer under slavery to money may become in time “the fair,'self−knowing man who cries, with smiles begotten of intelligence, to sun and stars, to death and to eternity: "Ye, too, are mine, and I your lord!"

Now Wagner outlines his practical program. First of all, the state and community must give the Theatre over exclusively to the artistic management of the artists themselves:

In the first place it would be the business of the State and the Community to adjust their means to this end: that the Theatre be placed in a position to obey alone its higher and true calling. This end will be attained when the Theatre is so far supported that its management need only be a purely artistic one; and no one will be better situated to carry this out than the general body of the artists themselves, who unite their forces in the art−work and assure the success of their mutual efforts by a fit conception of their task. Only the fullest freedom can bind them to the endeavour to fulfil the object for sake of which they are freed from the fetters of commercial speculation; and this object is Art, which the free man alone can grasp, and not the slave of wages.

Next, the state and community must arrange a common purse, so that no member of the public must purchase his ticket in the manner of a buyer of goods and services in a market:

The judge of their performance, will be the free public. Yet, to make this public fully free and independent when face to face with Art, one further step must be taken along this road: the public must have unbought admission to the theatrical representations. So long as money is indispensable for all the needs of life, so long as without pay there remains naught to man but air, and scarcely water: the measures to be taken can only provide that the actual stage−performances, to witness which the populace assembles, shall not take on the semblance of work paid by the piece ,a mode of regarding them which confessedly leads to the most humiliating misconception of the character of art−productions, but it must be the duty of the State, or rather of the particular Community, to form a common purse from which to recompense the artists for their performance as a whole, and not in parts.

Notice that Wagner prefers the particular community to the state apparatus as the operator of this common purse. No top down imposition, but rather a free association of free men contributing to the maintenance of the public theatre together. He even claims that when this is impossible, it is better to kill a theatre completely, than to allow it to run as a commercial venture. Let the community starve until they are willing to make the necessary sacrifices.

Dare we call this an Artistic Communism? For Wagner, the communal ideal is expressed not in the collective economic striving for the means and needs of slaves to be taken care of. Rather, it is in a shared public Art where the great visions of the universal fraternity of man shall be realized.

Art and its institutes, whose desired organisation could here be only briefly touched on, would thus become the herald and the standard of all future communal institutions. The spirit that urges a body of artists to the attainment of its own true goal, would be found again in every other social union which set before itself a definite and honourable aim; for if we reach the right, then all our future social bearing cannot but be of pure artistic nature, such as alone befits the noble faculties of man.

Thus eventually would every enterprise be guided by the spirit, motivated by its own intrinsic desire for joy and the affirmation of life. Thus would human institutions be guided not solely by the economic and military necessities of political power, nor by the logics and absolute doctrines of priests and scholars, but by the force of Love, which alone knows Beauty, which can be energised in time and space into Art.

And then, a remarkable conclusion, in which the fundamental force of Wagner’s Art is laid bare:

Thus would Jesus have shown us that we all alike are men and brothers; while Apollo would have stamped this mighty bond of brotherhood with the seal of strength and beauty, and led mankind from doubt of its own worth to consciousness of its highest godlike might. Let us therefore erect the altar of the future, in Life as in the living Art, to the two sublimest teachers of mankind: Jesus, who suffered for all men; and Apollo, who raised them to their joyous dignity !

In part 3 we will reflect on how to read this paper for the Dark Renaissance.